The strength of Varo’s The World That I Knew lies in its ability to sound ancient without ever feeling remote. Across ten reimagined traditional songs, the Dublin-based duo don’t just interpret history—they inhabit it. There’s nothing dusty or delicate here. These songs are lived-in, bloody-knuckled, and heartbreakingly present.

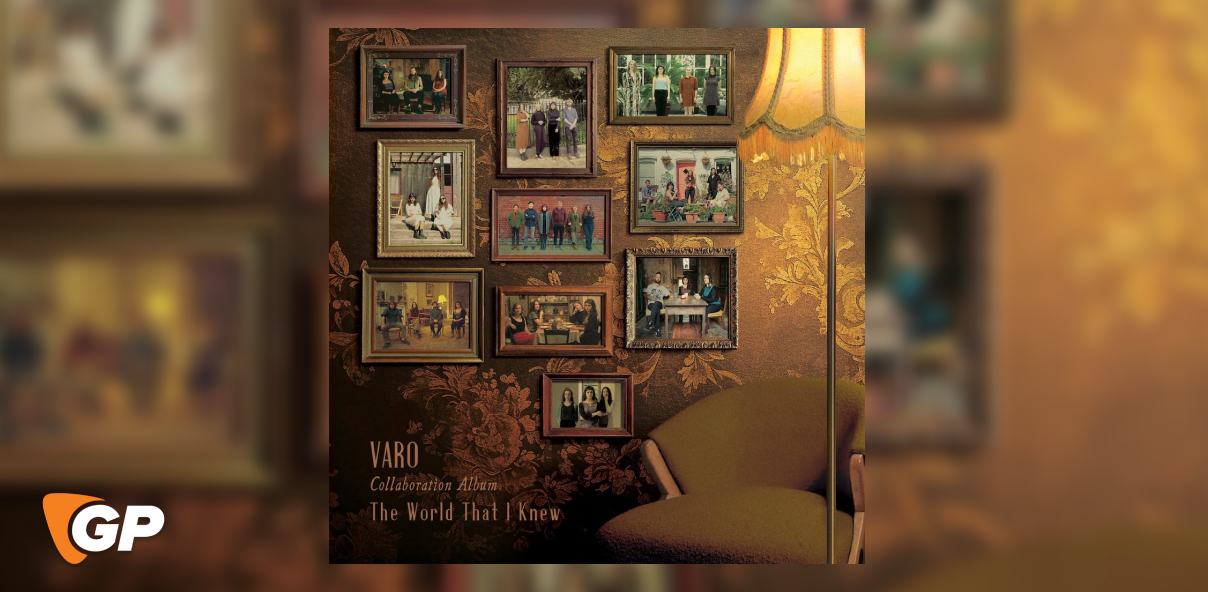

Lucie Azconaga and Consuelo Nerea Breschi, both outsiders to Ireland by birth but insiders by craft, are joined here by a who’s who of the contemporary Irish folk scene. Lankum’s Ian Lynch and Cormac Mac Diarmada, Junior Brother, Lemoncello, John Francis Flynn, and Anna Mieke all make appearances. It’s a testament to Varo’s quiet magnetism that these contributions serve the songs rather than steal them.

Opening track ‘Lovers and Friends’ sets the tone—a slowly unfolding piece that pulses with emotional tension, steeped in harmony and ghosted by loss. ‘Red Robin’, by contrast, lopes gently along, almost lullaby-like, until its harmonium drone and bowed strings nudge the track into eerier territory. Throughout, Varo revel in these quiet hauntings.

Producer John ‘Spud’ Murphy (Lankum, ØXN) lends a cinematic weight to the album, all smoke and shadow. Harmonium drones, subtle feedback, and field recordings fill the spaces between strings and voices. But for all the studio flourishes, Varo never lose the thread. The heart of these songs remains intact: tragedy, defiance, longing.

There’s nothing timid about the political edge either. ‘Work Life Out to Keep Life In’ is a standout, less a folk tune than a workers’ lament for the zero-hour age. Its tension is matched by the anxiety threaded through ‘Let No Man Steal Your Thyme’—a warning cloaked in beauty, its message sharpened by repetition.

The guest appearances enrich without overwhelming. John Francis Flynn’s breathy intensity lends ‘Green Grows the Laurel’ a funereal depth, while Junior Brother’s distinctive burr on ‘Skibbereen’ gives the classic emigration ballad a cracked, unnerving edge. Yet this never feels like a cameo-fest. The collaborators are woven into the fabric, not stitched on top.

Producer John ‘Spud’ Murphy once again proves to be Irish folk’s sonic alchemist. From the earthy fidelity of ‘Heather on the Moor’ to the reverb-drenched ache of ‘Alone’, his fingerprints are all over the atmosphere. He knows when to let the silence speak, when to let the harmonies bloom, and when to introduce just enough distortion to make something old feel thrillingly new.

By the time we reach the closer, ‘Alone’, it’s clear what Varo have pulled off. The World That I Knew is more than an archival project—it’s an act of reclamation. These songs aren’t museum pieces. They’re warnings, laments, spells.

That’s the real achievement here. The World That I Knew doesn’t pretend the past is prettier than it was, but it finds beauty in the cracks. It’s music for a country still talking to its dead.

A rich, reverent, and quietly radical record that confirms Varo as one of Irish folk’s most vital voices.