When you think about the illustrious Irish contributions to rock'n'roll names like Lynott, Bono, Gallagher and Geldof spring to mind, but when you look beyond the glamour, the name Dave Robinson can stake a claim as arguably making as big, if not greater, contribution to music than all of them.

If you spilled Dave Robinson's life onto a page in the form of a movie script, you'd be laughed out of Hollywood for trying to outdo Forrest Gump in terms of sculpting a story around so many culturally significant people, places and events. Unlike the Tom Hanks megahit movie, Dave Robinson's life story is true. It binds The Beatles and drum'n'bass and Bob Marley and Madness together in ways you could hardly believe.

Like most Irish people of his generation, amateur photographer Dave Robinson got on a boat to England in search of an occupation. "I went to England to see if I could push my career forwards and I got a job at Rave magazine, which was a Smash Hits type magazine. They did a series on The Cavern. The Beatles were not that huge at the time, but they were big in the Cavern. I did about 10 bands in the Cavern as part of a Liverpool piece and the Beatles were one of the bands at lunchtime that I took some pictures of. They were nice guys, but nothing particularly special. All those scally Liverpool bands were all full of chat and banter. They were all playing very similar songs - R&B songs from America, Chuck Berry. I remember them being pleasant. Paul McCartney was a very nice guy and John Lennon wasn't very talkative."

Before long Robinson would be rubbing shoulders with the Liverpudlians' rivals, The Rolling Stones, as the official photographer of their debut Irish tour. "They were a bit more unpleasant," Robinson laughs, recalling the experience of shadowing the Glimmer Twins. "Although they had agreed to me doing the pictures they weren't going to be very cooperative, and that was their style I suppose at the time."

You would think that taking pictures of the two biggest British bands of all time would have you set for life, but it would seem that it was not only bands who got less monetary rewards than they were worth in the '60s. "It pisses me off, of course, that I never kept the negatives. They all went to the magazine so I never kept anything that I could monetise."

Having established himself as a reputable photographer, Robinson took the unusual decision to return to Ireland and immerse himself in the the thriving but less glamorous world of Irish showbands, but without this quirky career move he wouldn't be able to count Dickie Rock amongst his Facebook friends.

"Spotlight Magazine was a showband magazine at that time. I became their resident photographer and went around the country shooting showbands and taking the their publicity photographs. That was very advantageous. In the early days they used to order original prints, they'd order 1000 prints and I'd be up all night printing like a mad person."

Robinson's London look caught many a farmer off guard as he went about his business with Spotlight. "Coming back from London, I had long hair which was moderately unique in Ireland at the time, particularly in the country towns. People would stare at you in the street and be a bit amused by your look."

"Dickie Rock, who's still a Facebook friend which is really odd to contemplate, Joe Dolan and The Drifters, The Freshmen - every town had its own band. I met Henry McCullough originally when he was in a band called Gene and The Gents. He was in a couple of early showbands before he eventually became famous for playing with Paul McCartney and The Grease band." The Portstewart guitarist would go on to play Woodstock with Joe Cocker, appear on hits such as Live and Let Die as a part of Paul McCartney's Wings, as well as appearing on Pink Floyd's 'Dark Side of The Moon' and many other significant releases throughout the '70s.

Despite enjoying the financial rewards of his all-night printing sessions, Robinson knew that the appeal of Irish Showbands could only last so long and he had his eye on making his next move. Even though he didn't know it at the time, Robinson was about to be a pivotal cog in a the youthquake that was punk. But first, Robinson would play a role in the development of Thin Lizzy.

"I worked with a guy called Tony Boland who opened the first beat club in Dublin Sound City on Burgh Quay. Before that it was Tennis Clubs. Tennis Clubs in Dublin were very popular and you had mini-showbands who learnt the charts and a few R&B songs...very similar to the Liverpool bands.

"After Sound City a few clubs sprang up in Dublin and elsewhere, and there was a little bit of a circle. Bands could hardly support themselves. One of them of course was a band called The Black Eagles who had a lead singer called Phil Lynott. He was about 15 at the time. I think the manager of the band was the drummer's father and he got them into blue blazers and black polo-neck sweaters. They all looked the same, but Phil had white gloves, that was his standout feature and of course he was very popular with young girls. Unusually popular, the boy had it from an early age.

"He was always a standout and very, very chatty. He could chat for Ireland and he didn't change over the years. He wrote a lot of better songs than people think, people think The Boys Are Back in Town and a few others. He actually wrote quite a few, if you look back through his catalogue, some of which were never recorded. I was a fan of his songwriting, and songwriters are something that I've really specialised in. I'd find a songwriter and if he could sing it didn't really matter whether he looked like Frank Sinatra or not. I followed the songwriters and I helped promote a lot of them when I started Stiff Records."

Stiff Records, like most of Robinson's career-moves, was born out of his precise photographers mind which allowed him to see things other people couldn't see. It was something that Robinson was able to twin with business acumen.

"I'd been in America tour managing with Jimi Hendrix, The Animals, those kind of bands, all managed by a guy called Mike Jeffery. I came back to London thinking that the management was not very good, they didn't look after the bands. The record companies were interested if you had a hit, but they didn't really help a lot and the groups were being sent on very random tours in America. Travelling constantly against the clock, people weren't working out how the tours could flow simply.

"I came back with the idea of a management company were I would do it properly. I started managing a lot of unknowns and getting them signed to major record companies. I always thought that when you signed with a major it was all gonna be easy, they knew what to do, they'd publicise the band etc. and I found that they weren't very clever. So I decided I could do it better and that's where Stiff came from. Obviously the name was taken from a record that failed miserably so we'd call ourselves Undertakers for the Industry."

Stiff Records would go on to release music by Elvis Costello, Ian Dury, The Pogues, Madness, and many other household names.

"I started Stiff Records in 1976 so I'd been through quite a bit. When I was in Dublin I'd also worked in a printers, so I knew a bit about printing, a bit about photography. I'd been on the road with bands. I'd been a tour manager and I'd been a manager so it was a culmination of all those experiences that got me into an independent record label.

"The label got a name for itself because there was a great DJ on BBC called John Peel and he was up for any kind of new music. He liked the label and he played a lot of our records, which was very helpful and launched us into being a threat to the majors. We were the independent label that people wanted to sign to.

"People could come into the office at any time and we would listen to their material. We signed Wreckless Eric, he was drunk the day he fell into the office. He fell on the floor - not the most auspicious entry, but he he gave me a cassette which contained the song Whole Wide World which is a song a lot of people have related to and has been a cult success ever since. There was a lot of those kind of people happening - Kirsty MacColl, eventually The Pogues - but we were always looking for the unusual but great songwriters."

"I always thought the songwriting was kind of the folk music of my time. I was interested in The Beatles from a fan point of view. I thought that their music was songs about the social life of Liverpool and England, generally. I've always been interested in people writing about the life that they are living rather than the fantasy of love stories, though I'm not against it. I've thought that a documentary of the times is part of the requirement of good music. And when you have a band that can write it means that you're not searching around for a new song for them to do. So, if they are doing their own songs and they are good enough, it makes a small label ethos much easier."

"I think Ian Dury had the opportunity to be huge actually, because Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick was number one around the world. In America it was going up the charts when they were touring with Lou Reed, who didn't like them, but that's another story," says Robinson reflecting on who he thinks should have had a bigger career from the Stiff Records roster.

"We were signed, licensee-wise, to Arista Records, owned by Clive Davis, a very talented guy at picking records - Whitney Houston and various other people. He was fairly middle of the road but he liked Janis Joplin and he'd been involved with the signing of Bruce Springsteen at Columbia.

"Unfortunately, he went down to a gig in New York at The Bottom Line that Ian was playing and he went into the dressing room. I tried to stop him. The band had just finished. I said 'Clive, you don't want to go in there they have a bit of a row sometimes after the show, we normally leave them 20 minutes and Ian needs to get dressed.'"

"But Clive felt that he knew better and he wanted to go in early because he had somewhere else to go. So he went in and a guy called Cosmo Vinyl who went on to work with The Clash - he was Ian's kind of mouthpiece at the time - was fascinated by Clive Davis and wanted to know who had made Clive's jacket.

"So he kind of rough-housed Clive a little bit to open his jacket to find out what the label was. It was a bit much, Clive hated to be touched and freaked out completely and the following day he and his partner fired all of my bands off of the label and stopped the promotion of the records.

"The records were doing really well, probably would've been about top ten records, and they were stopped in their tracks because they said that my staff had assaulted Clive, which was anything but the truth. I told Clive not to go in there so we got into a very difficult situation. Luckily I was able to get out of it through the help of Sony Records who were interested in signing Stiff Records, but he never recovered the momentum of the singles."

"He's a cult hero to a lot of people, but it was when he was with Chaz Jankel - when he came along, that was the chemistry that made the tracks that people talk about. Ian wrote the words and Chaz did the music and it was that combination that made it work - neither one without the other were that commercial.

"Ian was always difficult to get along with because he'd had a very difficult childhood with the polio and everything. He'd been sent to a special needs school, when special needs school meant they dumped every poor kid who had anything wrong with them into the same building.

"Ian had a good brain, a high IQ, and he was in with people who used to beat him up a lot so he had a bit of a chip on his shoulder. He wanted to always be the boss...when he got a bit of fame it was hard to get him to relax and be part of a team and that was always one of the problems with him. And that was a shame, but people who know and hear that 'New Boots and Panties' record, what an incredible record.

"He was always very well meaning, Ian, but he could be very difficult to get along with. It's the story of artistic people."

As well as creating a platform for artists to grow, stiff Records also created a hothouse for every aspect of the record business from marketing to video production.

"My chief cameraman on about the first 8 Madness videos was a guy called Roger Deacons, he's just won his second Oscar for cinematography (1917). We worked together for over a year making Madness videos and he's always told me it was that experience that got him an idea of how good he could become as a cinematographer."

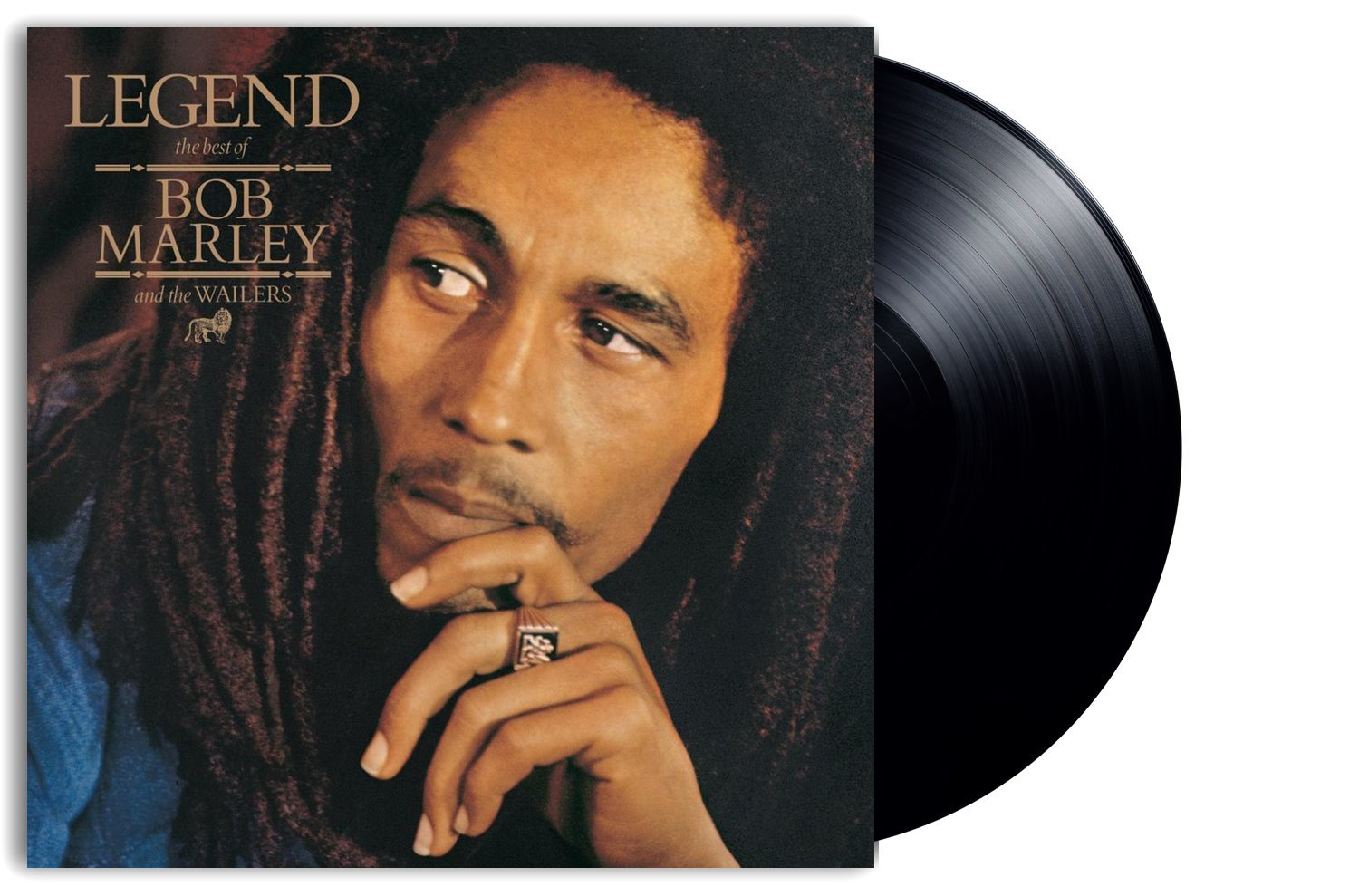

Having successfully launched the careers of numerous household names, the major record labels eventually decided that they required Dave Robinson's expertise and Island records eventually won the battle for his signature. It was a move that would see Robinson working with acts such as Frankie Goes To Hollywood and U2, and would present him with perhaps his career highlight - compiling Bob Marley's 'Legend' album, which has sold in excess of 44 million copies to date.

"I really loved his [Marley's] music and I got an opportunity to put out the record and market it. Although he was moderately famous he was really a cult figure in terms of record sales, so Legend has changed that quite a bit.

"A 'greatest hits' is a marketing exercise, in a lot of ways. You're able to pick and choose some of the hits and some of the obscure stuff, that's great. A more objective person who is outside the circle, if they know what to do they'll make a better job.

"I did a lot of 'greatest hits' records over the years for major labels, but 'greatest hits' are mainly big, big successful sellers because the artist is dead, because then they don't interfere with the person putting the record out.

"A lot of artists' idea of their greatest hits are not always what a person like me is able to do when there is no opposition from the artist. I was looking at a second 'greatest hits' for Van [Morrison] at one point. I came up with a running order for him and he didn't like it at all. He said, 'I'm not having that, that's not my greatest hits.' I said, 'Well write your greatest hits down for me and he wrote a set of songs that were good Van Morrison songs, but to my mind were not what the public would major on.'"

However, it wasn't simply the song selection and running order that made 'Legend' such a success. Once again, it was Robinson's photographers instinct which put the subtle into the hard sell.

"When Island had signed Bob he was inclined to have a very military look to him. He was always photographed in camouflage clothes and he looked a bit hard. I think a lot of people thought he didn't like white people which is not true, but they pushed him in the wrong direction [visually] I thought.

"To sell a 'greatest hits' to the public you've got to find the right kind of vibe, the right look and feel. It took us about 3 months to find that picture because I was looking for a softer picture, a more contemplative picture. That happens to be Haile Selassie's ring he's wearing, and that was the only picture I think that had that ring in it.

"So, the whole feel of it was softer and though all of his songs were quite revolutionary, he was singing about the world and what it should do, but they were all very interesting lyrics if you go into them, but at the same time this was a set of songs that were more accessible."

When Robinson moved to Island Records he also found himself working with U2, a band which he had opted not to sign for Stiff Records as their manager Paul McGuinness' expectations and goals were beyond the financial muscle of an independent record company. Robinson had suggested that Island would be a more suitable home and now he found himself in a position to provide U2 with the backing they desired to achieve their goals

"Island saw the promise of U2, and a few years later U2 sort of blossomed. And then I took over the record label and was able to put them onto TV advertising. I was a fan, I could see that TV was the way to a lot of people discovering bands. Discovering bands the rest of the time was a slow and tortuous job and you had to play every toilet in the country over and over again, but TV would short circuit that. I worked U2 and Island onto television, which culminated with Live Aid. When Live Aid came out U2 were on the up, and obviously that was a big success."

Robinson believes the importance of Live Aid on U2's career cannot be underestimated. "U2 were growing at that time and they'd just started to have really big hit records. That show went worldwide and if you did something memorable, which in the case of Bono was getting some girl - who I believe was his cousin - up onto the stage [to dance], then the rest of the world saw that musical entity as something that was all encompassing with the world generally. I suppose Queen and U2 had the biggest success out of that Live Aid situation."

"I was always impressed with Bono as a marketing man. Not only was he good out front, there's always a guy in the band who could be the manager, who has the vision of using his industry, the tools he has around him, to make his ambition come true and Bono was very much in that ilk."

"It was probably four years from when they were signed to when they really started to make a dent in the charts. They worked hard."

Find out more about Dave Robinson and The stiff Records story in Liberty Hall on Saturday February 29th. Tickets here.