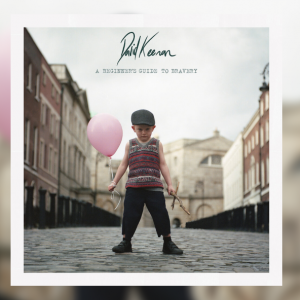

Hinted at in 2018, recorded in 2019, finally released in 2020: from the way ‘A Beginner’s Guide To Bravery’ has made its appearance, you’d think that David Keenan was not that bothered about it.

It’s probably truer to say that Keenan doesn’t privilege the making of an album over any other creative act as part of his voyage of artistic discovery. When we last spoke to him, he described the record as a map of his personal evolution. It’s best listened to in that context, as a kind of musical bildungsroman, and what a development it traces.

On one hand Keenan belongs to a tradition of romantic singer-songwriters that stretches from Damien Rice to Mike Scott all the way back to Dylan. On the other, he’s utterly unique. It’s telling that the album’s opening track, James Dean, is not a paean to Hollywood glamour, but a skewed look at small-town Irish life: “I had a dream that James Dean was alive and well today, looking for the quiet life, working for Irish Rail”.

Having left school before his leaving cert, Keenan has an autodidact’s ravenous appetite for imagery, experience and learning. So it’s not surprising that lyrically, the album contains work of extraordinary ambition. The word painting in the opening verses of Love In A Snug is superbly evocative, asking “can you hear the the clicking of bootheels on barstools, and see the bald chalkless tips of the pool cues, and the three-bar heater that’s gasping for air?”

But in an album of remarkable images, those lines are nothing special. On Origin Of The World, Keenan sings of discarded love: “I’ve emptied my skull of stale symbolism; from my fingers I’ve scrubbed you like a nicotine stain”. On Good Old Days, he counter-poses nostalgia for the past with the reality of its poverty: “I heard an old one speak of the emergency, hiding coal beneath a baby in its pram”. And that’s before he casually mixes in lines from TS Eliot, as he does on Tin Pan Alley.

At their best, these songs are both intimate and anthemic, drawing you in with softly-sung intros before building to soaring crescendos during their choruses. However, where Keenan’s lyrics speed off on flights of fancy, his music doesn’t always keep pace. The plangent strings on some tracks dress up buskers’ chord progressions, and the arrangements can be frustratingly repetitive. After 4 songs of guitars and drums on the first half of the album, the upright piano on Tin Pan Alley sounds almost exotic. And the hauntingly sparse ambient backing in Origin Of The World is not well served by the ever-present acoustic guitar laid over it.

Furthermore, there are so many slow-paced songs in the album’s final third that even Keenan’s hyperactive vocal lines can’t sustain its energy. Evidence of Living has more than its share of memorable lines, including ones describing a character with “a face like an old painter’s radio”. But coming as it does after two similarly downbeat tunes, the unadorned piano that provides its musical foundation feels listless – at least until the song finally bursts into life in its final minutes.

Newer tunes like the The Healing feel much more developed musically, with rhythmic and harmonic shifts that are complex enough to match the reach of Keenan’s words. The song has some characteristically bold images. But what gives it power is its sweetly urging chorus of “hold me; I’m only a moment away”, and the way that it hints at a universal sense of connection, drawing together singer, listener, and their shared experience of life’s great events: “somebody dies; a child gets born”.

The album’s epic closing track, Subliminal Dublinia, repeats that trick, starting as a walk past the rough sleepers and dock workers of the city but ending as a rousing call for “a revolution of the mind and of the soul and of the heart”. Keenan’s revolution is political, imagining a world where “no one dies of the cold while others reap what they’ve sold”. But it’s also personal in the most transfigurative sense, ending with the line “occupy the city with original ideas” repeated over and over.

With those words ringing in your ears, doubts about the musical strengths of the album feel like quibbles. ‘A Beginner’s Guide To Bravery’ heralds a talent of huge promise. There’s more than a trace of Jeff Buckley in those swooping vocals, but the lyrics they sing are more strongly redolent of those of early Tom Waits – and that’s pretty good company for a debutant to be keeping.

With its cast of lovelorn dreamers, barflies, and outsiders, the album remakes the humdrum world in a way that ultimately feels transformative rather than escapist. Like Waits, Keenan has the ability to conjure up a more fantastic version of the everyday, to make his “pyrotechnic rhymes” into fireworks to light up your life. If he can build musical muscle to better hold the weight of those freewheeling lyrics of his, his next one will be truly sublime.