Oh, the trials of middle-aged millionaires. Isolated in their affluence, how can they prove that they still understand what it’s like for us, that they still get it? They can look to the music of their youth for authenticity, as Bono has tiresomely done, but in doing so they show only how out of touch they are. No one wants to hear about how things were better in your days Granddad. So it’s not a promising start when the very first song on Bruce Springsteen‘s first album of his own originals in many years has him singing of “hitchhiking all day long, a rolling stone just rolling on”. Are these just the cliches of a writer too far removed from the world to remember what happens in it?

No. Springsteen practices something that Bono has long forgotten – the art of imagining the lives of others, of singing in the first person about experiences far removed from his own. The hitchhiker’s not a stock character, but an emissary sent on a journey into the idea of America. Those western stars are not the ones in the sky, but the archetypes of the films and music that made modern culture.

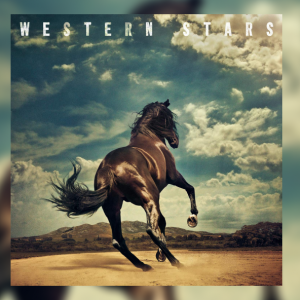

The tropes of classic rock are everywhere on ‘Western Stars’. It’s an album full of wanderers, of truckers and bikers traveling lonely highways, of “summer girls in the parking lot”. Springsteen uses those tropes in the same way Tom Waits does on his early songs, looking through them with a cold eye that finds just the right phrase to capture the hurt at the heart of it all. The crane operator in Tucson Train may recall Campbell’s Wichita Linesman, but he’s a far more bruised character, recalling that “We fought hard over nothing; we fought till nothing remained.”

And like Waits, Springsteen uses the lyrical anachronisms of classic rock to summon the prelapsarian optimism of an earlier America. The diner owner in Sleepy Joe’s Cafe starts his business after the war, but it’s the second world war and not the stalemates of Afghanistan or Iraq. There’s a sunset sweetness about this, a feeling that these characters are not the pallid ghosts of nostalgia, but figures in an a huge elegy for a nation.

The stuntman in Drive Fast, Fall Hard, with “pins in my ankle [and a ] steel rod in my leg…looking for any kind of drug to lift me up”, talks about finding a way to make the broken pieces of himself and his lover fit. But you feel that the breaks he means are bigger than he is, that they’re the tectonic cracks that have split a country from itself. And it’s no surprise in There Goes My Miracle that the miraculous figure appears suddenly but walks away, against a softly despondent chorus of “look at what we’ve done, look at what we’ve done”.

Nowhere is this more poignantly captured than on Hello Sunshine, which plays with the idea of journeying as a metaphor for freedom. The desire for the empty road is a staple of American music, but here it’s cast as a product of the vast emptiness of the continent itself – and by extension of the society in it. As Springsteen sings, “I always loved my walking shoes, but you can get a little too fond of the blues. You walk too far, you walk away…”

The album closes with an apt image, the empty pool in Moonlight Motel, abandoned and overgrown with weeds. It’s midnight in America: we can’t go back, so where do we go from here?

As a recording, ‘Western Stars’ is gorgeous. The production is lush without being overpowering, the acoustic guitars and pedal steel sound like they’re piped direct from a 70s Neil Young album, and everything’s swaddled in string arrangements that are plaintive but never cloying. Springsteen’s voice in particular is as woody as an old whiskey, the sweetness of the arrangements only highlighting the weight of experience it carries.

As a work of Americana, this is superlative, showing just how derivative lesser artists in the genre are – all the National’s albums together wouldn’t add up to it. But as a statement of continued relevance by an artist who’s decades in the game, it’s truly astonishing. A masterpiece from a man past retirement age. Bono, if only you could learn…