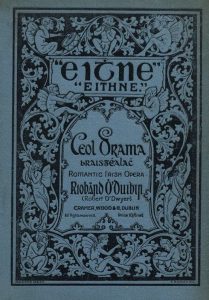

Gavan Ring and Robert O'Dwyer's 'Eithne'

October 14 sees Opera Theatre Company, with the RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra, present a concert performance of Robert O’Dwyer’s 'Eithne', an opera not heard for over a century. Revivals of neglected operas are rare at the best of times, but this one is even more exceptional as it is also the oldest surviving opera (and one of a very select number) in Irish. Last performed in 1910 at the Gaiety Theatre in Dublin, with a cast that featured the legendary Joseph O’Mara, 'Eithne' fell victim to changing fashions—as well as, arguably, shifting ideas of Irishness—and has been largely ignored, until now.

Singer Gavan Ring (Figaro in last year’s The Barber of Seville for Wide Open Opera), performs the role of Árd-Rí na hÉireann, the High King of Ireland. But that’s not all, as it’s also partly due to him that this opera is being brought back to the Irish stage, making this a very personal project—as he explains:

How did you first hear about this work?

I did a concert back in 2008 at the National Library of Ireland, in association with Opera Theatre Company, called ‘Gems of Irish Opera’. It was curated by Una Hunt, and she chose some of these forgotten Irish operatic works, like 'The Sleeping Queen' by Michael William Balfe, pieces by William Vincent Wallace and Charles Villiers Stanford, and in this mix were some sections from Robert O’Dwyer’s 'Eithne'. Throughout my life two of my great loves have been music and the Irish language, and when I came across this I was bowled over because I didn’t realise there was anything like that sort of music around, particularly from the early 20th century, and I was quite taken by how beautiful the music was, and how wonderful it was to sing, operatically, in the Irish language.

The piece stayed with me. It was two years later, when I decided to do the Doctorate of Performance in Music at the Royal Irish Academy of Music, looking for a subject for my thesis, that I honed in on this. There was one article that really copper-fastened my resolve to take it further, written by musicologist Axel Klein back in 2005, called ‘Stage-Irish, or the National in Irish Opera’. In it, to my surprise and great wonder, I discovered there was not just one Gaelic opera. There were actually three principal Gaelic operas written at the time: a piece by a guy from my own locality, from Caherciveen in Co. Kerry, Thomas O’Brien Butler, called 'Muirgheas' (1903), you had Robert O’Dwyer’s 'Eithne' (1909), and then Geoffrey Molyneux Palmer wrote an opera based on The Children of Lir, called 'Srúth na Maoile' (1923). I couldn't do all three, but 'Eithne' stood out, in terms of musical influence and where it’s situated culturally as well, and Robert O’Dwyer was an interesting character himself. Then the orchestral score became available in 2012 when the National Library purchased it, which made it possible for the opera to be put on (theoretically at that stage) at full scale. I did a contextual study of the opera, and its composition, and fashioned a new vocal score that centred around assisting potential performers.

The piece stayed with me. It was two years later, when I decided to do the Doctorate of Performance in Music at the Royal Irish Academy of Music, looking for a subject for my thesis, that I honed in on this. There was one article that really copper-fastened my resolve to take it further, written by musicologist Axel Klein back in 2005, called ‘Stage-Irish, or the National in Irish Opera’. In it, to my surprise and great wonder, I discovered there was not just one Gaelic opera. There were actually three principal Gaelic operas written at the time: a piece by a guy from my own locality, from Caherciveen in Co. Kerry, Thomas O’Brien Butler, called 'Muirgheas' (1903), you had Robert O’Dwyer’s 'Eithne' (1909), and then Geoffrey Molyneux Palmer wrote an opera based on The Children of Lir, called 'Srúth na Maoile' (1923). I couldn't do all three, but 'Eithne' stood out, in terms of musical influence and where it’s situated culturally as well, and Robert O’Dwyer was an interesting character himself. Then the orchestral score became available in 2012 when the National Library purchased it, which made it possible for the opera to be put on (theoretically at that stage) at full scale. I did a contextual study of the opera, and its composition, and fashioned a new vocal score that centred around assisting potential performers.

About 2-3 years into that I met up with Fergus Sheil (artistic director of Opera Theatre Company) and he became really interested in my research. Eventually then, once the doctorate was finished, we decided to apply for Arts Council funding under the Making Great Art Work scheme, and secured enough to put on this concert performance.

It’s been a bit of a journey, a lot of people have been involved in it, but we’re here now in this wonderful position… it’s like an archaeological excavation, because we’re hearing this for the very first time since 1910: it’s quite special.

Is the libretto of 'Eithne' like any other works you’ve read in Irish? Did the story connect to anything you already knew?

Yes, absolutely. It’s in the tradition of Irish fairytale and folklore, like the stories of Oisín and Tír na nÓg, or Cúchulainn and the Red Branch, Medb and the brown bull of Cooley, the Tuatha Dé Dannan, other Irish legends like Deirdre of the Sorrows: all these wonderful stories that so many Irish people will have grown up with. The great thing about this is that I’d say the majority of those in the audience will be able to relate to the world which this opera inhabits. It explicitly involves Tír na nÓg as an actual place, so it’s a very familiar imaginative space for Irish people. So many times you go to operas, even Handel or early Mozart operas, based on Greek or Roman mythology, and sometimes the references are a little bit left-of-centre for us to grasp onto, but this draws absolutely from the fairy folklore tradition of Celtic Ireland.

What else can the audience expect? What’s the music like?

There are some stonking tunes in it, you go away from rehearsals just whistling them, it’s that sort of a piece, you know? Being honest, there’s a bit of music out there that sometimes gets unearthed and we come away from those kinds of concerts sometimes thinking ‘yeah, well I understand why it wasn’t heard in 200 years!’ but this is different—it’s really good.

There’s this lovely mix, a symbiosis with the European art music tradition of the time, so you’ve all these wonderful influences swirling around the piece, there’s Strauss, there’s Verdi, there’s Wagner, there’s Debussy, there’s these beautiful international influences, and all the while you’ve this wonderful contour of Irish traditional melody going through it as well. Now, I’m not going to stand here and say the piece is perfect, it was only his first opera, but it was a real statement, and I think peoples’ imaginations will really be inspired by what’s going to be on offer.

We’re coming up to the European Year of Cultural Heritage in 2018. Can a piece like this ask questions about how Irish culture, and cultural heritage, is perceived?

We’re coming up to the European Year of Cultural Heritage in 2018. Can a piece like this ask questions about how Irish culture, and cultural heritage, is perceived?

Absolutely. When this piece was conceived, it was backed up by real heavy-hitters in Ireland, Douglas Hyde, Countess Markiewicz, the Lord Mayor of Dublin, Vincent O’Brien, Michele Esposito, and of course institutions like Conradh na Gaeilge… It was seen as a real statement of Irish nationhood. This cultural statement that 'Eithne' was making at the time was very much an international one, very much a European one: that we have this wonderful Irish culture and folklore and music, and this incredible indigenous culture, and we’re showcasing it via an international, European platform to assert ourselves as a nation within the context of the world and in the context of being a European nation, a part of the European cultural canon. I think it’s interesting that this question still is very much in the ether, especially with everything that’s going on at the moment, and how we sometimes see our culture as somehow confined to the gates of our wonderful country, but it’s far broader than that, it’s far more cosmopolitan, it’s far more European, and from that point of view it’s really interesting.

Every day I wake up with a smile on my face thinking that we’re actually going to be doing this. As far as I’m concerned, what will happen on October 14th will be historical; we’re bringing a piece to life that has been dead for over 100 years and, with all the cultural connotations and the era of centenaries that we’re in, this is a really historical occasion: it’s going to be brilliant.

Eithne by Robert O’Dwyer will be performed at the National Concert Hall, Dublin, on Saturday 14 October at 8pm: http://www.opera.ie/whats-on/eithne