Welcome to Fascination Street, where musicians wax lyrical about their favourite artists. David Tapley of experimental sound merchants Tandem Felix explains to us how Beck influenced him and helped shape his approach to making his own music. Take it away David.

Born in 1990, I missed most of the MTV hype surrounding Beck when he released his smash hit Loser. He was pegged as being the voice of his generation, a generation of slackers and layabouts. He always eschewed this label. "Slacker? I don't even have time to slack. I'm just trying to scrape together enough bread for a burrito". Nevertheless, he spoke to a lot of the supposedly disillusioned adolescents of early ‘90s America with his sardonic twist on hip-hop and his surreal humour.

He came from a family of artists and musicians who all had a great influence on Beck's career - and still do. His grandfather Al Hansen's collage art was an instrumental influence on Beck's use of samples - the idea of take a snippet from one medium and re-purposing it for another is the definition of Beck's entire career. His father, David Campbell, was a very successful composer and conductor, who had worked with people like Bob Dylan, Marvin Gaye, Cat Stevens and Carole King. He has worked with Beck on several occasions. If you hear any semblance of a string part on a Beck track, you are hearing a father and son collaboration. His mother Bibbe was an Andy Warhol superstar who ran the famous Troy Cafe? music venue in the '90s where her son got most of his first gigs, setting his guitar on fire and blowing leaves around.

When Beck, first took the stage, his appearance and demeanour was every bit as ramshackle as his music. Walking on stage at LA open mic nights with a leaf blower, clad in torn flannel and donning a detuned acoustic guitar, he earned the nickname “Farm Boy" from the rest of the scene. His shtick was a collage of folk-rock and punk riffs doused in country flavour and hip-hop vocals, a great contrast to the well-polished singer-songwriters he was preceding and proceeding.

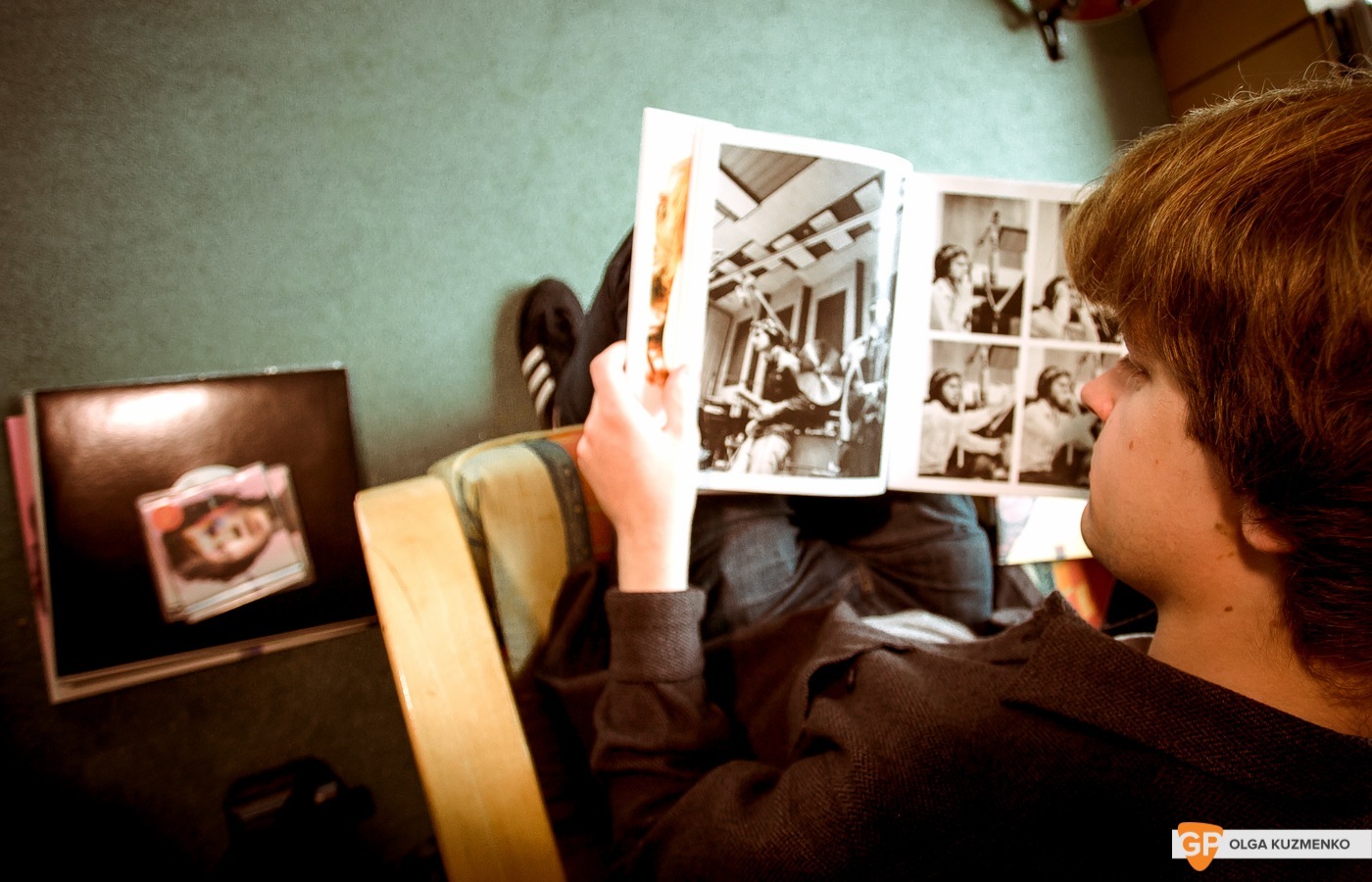

I first heard Beck in my early teens. Someone in my homestead possessed a copy of ‘Odelay!’ (1996) on cassette. Looking back, it seems like a fitting introduction - first hearing the derelict and dilapidated music of my soon-to- be hero on a rapidly deteriorating piece of magnetic tape. To this day, it remains my favourite record of his and definitely the first port-of-call for the uninitiated or non-believer.

‘Odelay!’ really shaped how I made music when I began. The sampling and drum looping present on songs like The New Pollution and Hotwax opened up my eyes to working alone and slaving over musical detail. As he moves from album to album, his purpose seems to change like the weather. In the space of his first five major-label records, he jumps from anti-folk to white-boy hip-hop, to Brazilian tropicalia and Bossa Nova to Prince-esque porn groove; it's as if he needs to get a stamp for each genre mastered in order to redeem his loyalty card for a free coffee. Not only does he jump from style to style, he does it with such ease and clarity.

2002, saw the release of ‘Sea Change’, which was the first record of his I was able to buy when it came out. It was like his colour-changing chameleon ethos was in overdrive, but its colour this time was slow pensive folk music. A man who one record previous was singing "Turn up the heat til the swimming pool boils" was now singing things like "These day I barely get by but I don't even try". This album, 'Sea Change', is one of my all-time favourites by any artist. So sweet and soft the music, it draws me in any time I listen, especially around bedtime. My girlfriend admits that if she listened to it late at night, she would be out cold in seconds.

In 2006, I went to see Beck play for the first time in my life at Marlay Park. He walked onstage to Loser playing over the PA, with long blonde hair pouring out from under his cowboy hat. Peering over his shoulder at the back of the stage was an exact model of the goings-on at the front of the stage; a puppet replica of Beck and his band, like something from a Charlie Kaufman film. Mimicking every movement, every syllable, every guitar change, puppet Beck projected as much sparkle as his human counterpart did.

In the latter part of the set, real Beck beckoned the introduction of a wooden dinner table. The backing musicians sat around the dinner table eating salad and drinking wine while their band-leader played some of the more tender numbers, before launching into the percussive knife-and-fork jaunt, Clap Hands, using wine glasses and dinner plates as beats and bells. At the interval of the show, two grizzly bears ran out onstage to fornicate with the instruments and perform a vast array of wrestling moves on each other. The whole concert was yet another glimpse of Beck tapping into as many media as possible.

When I was 13, I grew my hair long so I could look like Beck. When I was 14, I bought a harmonica so I could play like Beck. When I was 15, I went to see Beck play for the first time. I'm 24 now and if I could buy Beck bed sheets, I would.